The Sinking of the Sultana

140

years later, Sultana disaster

still haunts historians

Two survivors were from Jefferson County, Ind.

Editor’s Note: Around 2 a.m. on April 27, 1865, the steamboat Sultana exploded while passing north of Memphis, Tenn., along the Mississippi River. The tragedy claimed more than 2,000 passengers’ lives, most of them recently paroled Union soldiers returning home from Confederate prison camps at the close of the Civil War. More than 400 were from Indiana, including a few survivors from Jefferson County. Largely forgotten because it occurred at the same time as Lincoln’s assassination, the Sultana disaster remains the worst shipwreck in American history. On this, the 140th anniversary of the tragedy, we present the story of the Sultana disaster.

By

Robert Gray

Special to RoundAbout

(March 2005) – It was August 1863 and the boasting

and bravado of 1861 of 30-day victories over Johnnie Reb or Billy Yank

had melted away. Reality came to the North and South through the battle

mists of Shiloh and Stones River.

|

|

March

2005 |

The savage battles of 1861, ‘62 and ‘63 had

decimated whole regiments in both armies. These losses could be replaced

by the Union, but not by the Confederates. The young men of ages 17,

18 and 19 who enlisted in 1861 with patriotic fervor were now 20, 21

and 22 years old. Many regiments that numbered 700, 800 and 1,000 men

now mustered only 250, 350 or 400. And now there was the draft. Young

men now understood the hazard of death and maiming as they watched their

older brothers return from Shiloh, Stones River and Vicksburg.

Southeast Indiana had a particular alarm in July 1863 when Gen. John

Hunt Morgan crossed the Ohio River at Harrison County and raided and

pillaged across several Indiana counties. Madison, Ind., was “sieged”

for several days, but Morgan was bluffed away and moved his troops eastward

toward Ohio.

The risks were well known by two young men of Jefferson County, Ind.,

who enlisted as “Recruit Replacements” in September 1863.

They were young – 16 and 17 years – too young to

enlist in 1861 during the patriotic bravado that marked the outset of

the Civil War.

Romulus Tolbert, 16, and John C. Maddux, 17, farmed in Saluda Township,

in western Jefferson County, and in July 1863 both joined what was soon

designated the 8th Indiana Cavalry as “Recruit Replacements.”

The two young men would share an incredible series of events unique

to only a few who fought and died in that terrible conflict. Both men

were assigned to Co. H of the 8th Cavalry. Tolbert was first engaged

at the Union disaster at Chickamangua Creek, Ga., in late September

1863.

It took the Union Army more than three months to lift the siege of Union

forces after Chickamangua. Tolbert and Maddux, who went to the 8th Cavalry

Regiment directly after Chickamangua, were in continuous cavalry picket

service from Stevenson, Ala., to Browns Ferry, Tenn., during the siege

that lasted until January 1864. Then the Union Army was re-organized

and reinforced under Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and headed south

toward Atlanta.

The 8th Indiana Cavalry was engaged continuously during the summer months

of ‘64 along the Western and Atlantic Railroad south from Chattanooga

to Atlanta. The unit was vital to Sherman’s army in protecting

his supply line as he advanced on Atlanta. The 8th Indiana Cavalry skirmished

with rebel raiders almost daily and there were daily casualties.

|

|

This is the most famous photo of the Sultana, taken April 25, 1865, in Helena, Ark., just two days before the disaster. |

Sherman moved his army ever southward against Gen. Joseph

Johnston’s Rebels. In rapid succession, there was Ressca, Dalton,

Lovejoy Station, New Hope Church, Kennesaw Mountain. Confederate President

Jefferson Davis replaced Johnston with Gen. John Bell Hood, but on Sept.

1, 1864, Atlanta fell. Hood’s Rebel army was in shambles and was

forced southward and westward away from Atlanta.

Sherman and Grant conferred and decided Sherman would move his main

Union Army eastward, and this became the famous “Sherman’s

March to the Sea.” Most of the 8th Indiana Cavalry remained behind

to face the remnants of Hood’s Rebels and to protect the ever longer

supply lines between Chattanooga and Atlanta. This involved sharp, nasty

and deadly skirmishes, particularly along the Western and Atlantic Railroad.

One of these skirmishes was centered south and west of Atlanta near

Jonesboro, Ga., in mid-September 1864.

Tolbert was riding with Maj. Thomas Graham in a 50-man patrol near Cannelton,

Ga., in what was referred to as the “Kilpatrick Raids.” The

unit was attacked by Confederate Raiders from ambush near Owl Rock Church,

eight miles east of Cannelton. Tolbert was seriously wounded, and three

others of the regiment were killed. The Yankees were forced to retreat,

and Tolbert was captured.

Tolbert, seriously wounded, was taken to Cannelton and held in a private

residence for more than a week. After shot was removed from his jaw

and back, he was taken to a hospital facility in Montgomery, Ala., where

he remained confined for six weeks. About Nov. 1, Tolbert was taken

to Cahaba, Ala., and confined in the Cahaba Military Prison on the banks

of the Alabama River as a convalescing wounded.

Union skirmishing with Hood around Atlanta continued, and on Oct. 27

in a sharp action along the Western and Atlantic Railroad, Pvt. Maddux

was taken prisoner at Marietta, Ga. Maddux was also taken to Cahaba

Prison (dubbed Castle Morgan by the prisoners) and arrived in its confines

about the same time as the injured Tolbert.

Grueling life at the Cahaba Prison

The Cahaba Prison facility was formed in mid-1863 from a commandeered

half finished warehouse owned by one Col. Hill. The building had only

a partial roof and bunks were built six high to accommodate 660 men.

The structure was brick and measured 200 x 120 with a board stockade,

12 feet high enclosing an area of 15,000 square feet. Guards paced on

a plank walkway at the top of the stockade wall. The prison was serviced

by a six-hole privy, which exhausted into the Cahaba River, just west

of a confluence with the smaller Cahaba River. Cahaba had a number of

Artesian wells that offered continuous running water into the prison

building and hence to the privy.

Food at Cahaba prison was mostly rough ground corn meal, usually including

cobs and stalks and occasionally low-grade pork and rarely, rice. The

“New Yawker” gangs could sometimes have beef and cane sugar

as supplement from their illicit trade with the guards.

|

|

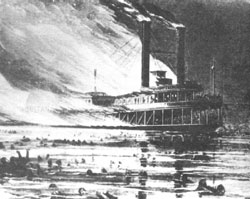

Photo courtesy of www.sultanadisaster.com This

oil painting of the Sultana |

Maddux and Tolbert were dangerously exposed in one respect.

hey were “occasional” prisoners in a sea of squads and whole

regiments (the 3rd Tennessee Regiment captured on Sept. 23, 1863, by

Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forest). This made them vulnerable to

“Raiders” and “New Yawkers.”

As with many military prisons, Cahaba held a number of predatory gangs.

New prisoners were soon relieved of their ready cash, watches, boots

and blankets. These were then traded by the predators to the prison

guards for extra food, soap, etc. These predator gangs were referred

to as “New Yawkers” as it was thought that most of these predators

came from Hookers “up east,” soldiers that had come to Sherman’s

army after the Union defeat at Chickamauga. There was a tacit approval

of these inmate predators by the rebel provost since they profited from

the thievery from newer prisoners, and the beaten and subdued prisoners

were thus less trouble.

Fate smiled kindly on Tolbert and Maddux in the person of “ Tennessee.”

“Big Tennessee” had been a wagon master in the 3rd Tennessee

Infantry. The “New Yawkers” had tried their predations on

soldiers in the 3rd Tennessee Regiment who were captured in late ‘63.

Big Tennessee was a large man, near seven-foot tall, barrel chested

and muscular, yet strangely kind by nature. He became a champion of

the oppressed. When the prison predators challenged “Big Tennessee,”

there was no contest and at the first outing with the New Yawkers, “Big

Tennessee” badly injured three “New Yawkers.” Then routinely,

“Big Tennessee” befriended many “occasional prisoners”

in Cahaba.

While at Cahaba Prison, the fate of Union soldiers lay with two Confederate

officers. By a strange fluke of command structure, Capt. Howard “H.A.M.”

Henderson had direct command of the prison, while Lt. Col. Sam Jones

commanded the prison guard and the Cahaba military district.

Henderson was a kind natured, even benevolent and caring Methodist minister

who sincerely tried to manage the prison as benignly as possible. On

the other hand, Jones was an embittered Louisiana regimental commander

who had surrendered to Grant at Vicksburg and was paroled.

Cahaba had a well run hospital facility that had been established in

the Bell Tower Hotel two blocks up Vine Street from the prison stockade.

The hospital treated both wounded Confederates as well as Union prisoners

at “Castle Morgan.” Tolbert could continue convalescence while

Maddux could be treated for diarrhea, which he had developed from the

rough and insufficient prison food. The hospital at Bell Tower listed

a daily population of 225 as the prison population drifted to more than

2,700 in early 1865.

Overcrowding, sickness, misery

By late 1864, as the population steadily rose, daily fare for prisoners

at Castle Morgan averaged per man only one quart of ground raw corn

(including cob and husks), one ounce raw pork or beef (often rancid),

occasional dried peas, and, rarely, rice. The men could sometimes supplement

food rations by trading with the guards. There was no cooking facility,

and the men were organized into 10 men messes, with one man from each

mess allowed outside the stockade once a day to cook. Cooking was over

an open fire in a bucket held on a stick.

Capt. Henderson worked continuously to better the situation for the

prisoners, and after extensive negotiations with Union Gen. Cadwalleder

Washburn, 2,000 each of shirts, pants, blankets, mess tins as well as

medicine came to Cahaba via steamer in mid-December 1864.

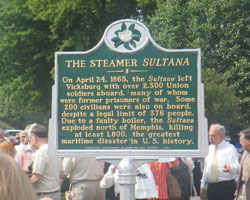

|

|

Photo by Bill Strong of www.phototour.com A

Vicksburg, Miss., marker |

Sadly, the relief shipment was soon bartered away to the

Confederate guards since the pressing need of the prisoners was food.

Thus, the men at Cahaba went into the winter months poorly clothed for

the uncommonly severe winter months of January and February. Suffering

in the crowded brick structure of the prison with only a partial roof

was severe.

The crowding rose sharply toward 3,000 men during late January and early

February 1865. The cases of scurvy and pneumonia increased. The hospital

at Bell Tower appropriated an adjoining house to accommodate the soaring

winter illnesses. Also, the inability of the Confederates to feed 3,000

men instead of a planned 660 men was evident. The ration of corn meal

fell to one pint per man per day, and any bit of bacon or beef came

very rarely.

As for Tolbert, his ability to continue his convalescence from his gunshot

wounds declined, while Maddux’s diarrhea from the rough, inadequate

food became chronic.

Still, in the midst of this increasing misery, there were acts of kindness

toward the Yankee prisoners. Amanda Gardner lived with daughter, Annabelle,

only a few yards from the stockade perimeter, and the two ladies passed

what extra food they had or could get through a hole in the stockade

boards to the desperate men. More over, the elder Gardner gathered and

passed on warm clothing to the Yankees as the hard winter weather continued.

She even cut up her floor rugs, blanket size, and passed them to the

Yankee prisoners as her gesture of mercy. But perhaps above all, Gardner

had books. She lent them without reservation to the deprived and miserable

prisoners. Even more remarkable, she had lost a son in the Confederate

Army in 1861.

In January 1865, the weather turned ever colder, but a more dangerous

event occurred on Jan. 23, 1865. Capt. Hiram Hanchett of the 16th Ill.

Cavalry and a small group of prisoners mutinied and succeeded in capturing

nine men of the prison guard inside the stockade.

An alerted Confederate outside guard succeeded in closing the outer

stockade gates. The guard commander was called – Lt. Col.

Sam Jones! Worse yet, the more moderate Capt. Henderson was away. Jones

ordered up two light artillery pieces and had them primed and loaded

and leveled through stockade ports at the 2,500 confined men in Cahaba.

The situation was on razor’s edge for an hour. Hanchett finally

gave it up, and the Confederate guards he had captured were released

from their confinement in the stockade privy.

Hanchett and his small band of mutineers were captured and confined

in a small dungeon in the Cahaba City Jail. Hanchett was probably murdered

by Lt. Jones. The mystery of Hanchett’s fate remains unresolved.

Considering the malevolent temperament of Col. Jones regarding Union

prisoners, it is surprising that Tolbert and Maddux did not die by cannon

blast at Cahaba military prison on Jan. 20, 1865.

Flood

threatens the prison

|

|

Photo

courtesy of This

photo of Tennessee survivors |

The winter continued to ravage the miserable prisoners

at Cahaba during February 1865. Maddux was in serious condition as his

diarrhea was chronic and worsening. Rom Tolbert’s wounds were incompletely

healed and his shoulder and lower jaw gave considerable pain in such

miserable circumstance.

In late February, events began to move swiftly for Maddux and Tolbert.

The winter weather abruptly abated, and the spring thaws brought a new

hazard – flood! On March 1, 1865, the Alabama River was in

flood stage. This also made for flood of the adjoining Cahaba River,

and by March 3, 1865, Cahaba prison was under three feet of water. Three-thousand

men faced drowning.

A prisoner delegation was allowed an audience with Lt. Jones, who assured

them that they may all drown as far as he cared. Sixty of the Confederate

guards under Jones’ command signed a petition to the colonel to

allow the prisoners to be confined on higher ground since they were

certainly of no escape risk in their present state of advanced disability

from malnutrition and a ravaging winter.

By March 3, providence relented, and the flood stabilized. Jones relented

and allowed small prison work details out of the stockade to gather

roots and other brush waste to be brought into the stockade. In the

days following, rest and sleep for the 3,000 confined men was on these

debris islands, rafters, bunks and the tops of the unfinished walls

of the prison shelter. The flood killed the usual running water supply,

and drinking water had to be brought in by boat.

The standing flood water within the stockade became putrid, particularly

with so many of the prisoners with persistent dysentery. The six-hole

privy was inundated, and the boards of the stockade perimeter was a

natural confinement for the flood water. The stench of human waste was

unbearable.

But momentous events same in a rush. Lee was approaching his destiny

at Appomattox. Sherman was moving up the Atlantic Coast toward Virginia.

John Wilkes Booth agreed to appear at Fords Theater in Washington, D.C.,

and, most importantly for Maddux and Tolbert, the newly promoted Lt.

Col. Henderson had secured agreement with Federal Col. A.C. Fisk to

parole and exchange men confined at Andersonville and Cahaba. The agreement

provided prisoner movement at once to Camp Fisk, five miles east of

Vicksburg, Miss.

The

long march to freedom

Tolbert and Maddux left Castle Morgan by river steamer about March 14

to Selma, Ala., where they boarded the Alabama and Mississippi Rivers

Railroad. The route was westward to Demopolis, Ala., thence to Meridian

and Jacksonville and on to Vicksburg. The rail trip was not direct since

the 700 men in Tolbert and Maddux’s draft often marched between

rail heads along the route, and the Federal soldiers marched the last

30 miles from Jackson, Mississippi toward Camp Fisk about April 10,

1865.

At last! Freedom, proper food, warm clothing and rest on clean Army

cots and recovery from a downward spiral toward death from malnutrition

and exposure while confined was a next step.

|

|

J. Walter Elliott |

The weak, emaciated prisoners were now in desperate straights,

and several of their group of 700 men had died along the way. There

were no rations for the prisoners. On the third day, exchange of prisoners

started, and Maddux and Tolbert staggered across the foot bridge spanning

the Big Black River and up the embankment to Camp Fisk. Freedom!

Federal orderlies helped the staggering wasted men to the open air commissary

where hogs’ heads were broken in and the prisoners accessed beef,

hardtack and brined cabbage. Tolbert and Maddux found themselves “absorbed”

by the soldiers of the 3rd Tennessee Infantry and “Big Tennessee,”

who was now only a wasted seven-foot tall scarecrow of a man.

About April 19, Tolbert and Maddux and others at Camp Fisk were issued

new uniforms. The sufficiency of food had worked wonders in only a few

days at Camp Fisk, but sadly, many of the newly released prisoners could

not hold down the suddenly plentiful food. Maddux was in particular

distress since his dysentery was now chronic and he could tolerate only

moderate portions of the plentifully supplied rations.

The spring rains were a plague since Camp Fisk had no shelter facility

for the wasted prisoners. The men foraged lean-to material from the

surrounding forests. Branches, logs and river reeds were used.

Capt. George Williams was preparing release rolls as quickly as possible,

and by April 20, several hundred men were sent the five miles by rail

to Vicksburg to be transported up river to Camp Chase in Ohio for discharge.

By April 20, both Union and Confederate knew the war was over, and there

was a rush to move the pitiful ranks of released men north to Camp Chase

as fast as possible.

|

|

John C. Maddox |

Further, by April 20, large drafts of Union prisoners from Andersonville, Ga., were arriving at Camp Fisk. The men from Andersonville were almost all gravely debilitated, starved and emaciated, in dramatic contrast to the men from Cahaba, who although badly debilitated were dramatically better of than the men from Andersonville.

Arriving

at the river port

On the morning of April 24, 1865, Tolbert and Maddux, along with many

other Indiana soldiers (the rolls were prepared by state), were put

on a train and taken the five miles by rail to the waterfront at Vicksburg.

There were three giant river steamers ready to accept them. But oddly,

all of the prisoners were marched across the gang plank of only one

of the boats. The steamer Olive Branch had backed into the flood-swollen

Mississippi and dug its side wheels into the current headed north with

700 men just before Tolbert and Maddux arrived at the Vicksburg wharf.

|

|

Romulus Tolbert |

The steamer Sultana had been at New Orleans on April 18,

1865, having been the vehicle that carried the news of Lincoln’s

assassination to the ports down river from Cairo, Ill. While at New

Orleans, chief engineer Wintrenger informed Capt. Cass Mason that one

of the new fangled tubed boilers was leaking. After discussions, it

was decided to head up river on the flooding Mississippi and manage

repairs at Cairo.

The Sultana had docked at Vicksburg in the evening of April 22, 1865.

Chief engineer Wintrenger told Capt. Mason that the inboard larboard

(port-side) boiler was now not only leaking but was now “warped.”

With such alarming news, Mason relented and sent for a boiler repairman

from Kleins Foundry at Vicksburg. The repairman wanted to install a

new boiler section but was overruled by Mason, who assured the repairman

and Winteger that the boiler would be repaired at Cairo. Kleins Foundry

installed a “patch” on the boiler.

Meanwhile, the Sultana business agent had been busy arranging transport

of the released Union prisoners from Camp Fisk to Camp Chase. Terms

of the negotiations were soon evident. All of the prisoners from Camp

Fisk would be boarded on the Sultana. All 1,700 or 1,800 or 2,000 – no

one ever knew for sure. The assigned limit for passengers on the Sultana

was 376.

When they boarded, the happy, homeward-bound soldiers gladly accommodated

to the grossly cramped conditions aboard the Sultana. Again, the men

formed 10 men messes and were “in place” wherever they were

assigned a billet, mostly on the exposed hurricane deck. The officers

fared better, being assigned quarters in the “grand salon”

on the boiler deck among the paying passengers.

Tolbert and Maddux, along with perhaps 2,000 other Union soldiers, crammed

every available space aboard their steamer, and by 3 p.m, the Sultana

backed into the flooded Mississippi and headed upriver, bearing happy,

relieved, sick Union soldiers toward home. Tolbert and Maddux were assigned

space on the boiler deck with barely enough room to lie down on blankets,

but nevermind, they were headed home!

Trouble on board

Within two hours of the voyage on the flooded Mississippi, it was necessary

for the ship’s company to wedge giant timbers under the floor of

the hurricane deck, since the deck flooring was dangerously sagging

from the weight of 1,000 men now quartered there (many of the 3rd Tennessee

and “Big Tennessee”).

The following day, April 25, the Sultana put in for ship's business

at Helena, Ark. It was here that a photographer was on a wharf boat

and set up to photograph the happy home-bound soldiers. Many of the

1,000 soldiers on the hurricane deck wanting to “be in the picture”

moved en mass to larboard. The boat listed 20 degrees, and a frightened

Capt. Mason begged the officers to move the soldiers to their assigned

billets to help right the listing boat.

When the Sultana arrived at the wharf boat in Memphis on the evening

of April 26, 1865, the inboard larboard boiler was again inspected,

and the patch seemed to be holding satisfactorily.

About midnight, the Sultana raised steam and moved across the flooded

Mississippi River to an Arkansas coaling yard, where the happy home-bound

soldiers helped the ship’s company load aboard more than 1,000

sacks of coal, enough for the upriver voyage to Cairo, Ill. Cairo was

to be a stopover on the way to Camp Chase, Ohio, where the prisoner

veterans expected quick release from their wartime service and their

captivity at Andersonville and Cahaba prison camps.

The steamer left the Arkansas coaling station about 1:30 a.m. on April

27, 1865. Many of the euphoric, just released Union prisoners had about

30 more minutes to live. A few more had several hours more to live,

while a pitifully few would survive the coming horror.

The Sultana crossed the flooded Mississippi and established up river

headway, close to the Tennessee side of the river. The Sultana steamed

six miles up river when a huge explosion occurred.

Perhaps 200 souls were blown immediately into the flooded river. Some

were badly scalded as well. Maybe 50 more had crowded around the boilers

for warmth in the unseasonably cold night. These were dead instantly

from the blast and scald. The blast created an immediate fire threat.

The flames were visible for many miles at Memphis, in Arkansas and upriver

to approaching down river bound steamers. Panic ensured, and 700 or

800 people jumped into the flooded river. Although panic prevailed and

memories failed with time, Tolbert and Maddux were probably among these

first victims into the river. The sudden mass of men in the water took

down even the competent swimmers among them, but Tolbert and Maddux

separated from the stricken and doomed mass and floated down river toward

Memphis with the debris.

There was a fitful effort on board to organize “bucket brigades”

to douse out the ever-spreading flames, now gaining momentum from fore

to aft. But spreading panic prevailed, and all but the prow area of

the packet was soon fully enveloped in flame. As the inferno moved quickly

aftward, even more souls chose to jump into the water rather than burn

to death.

The fire horror had mostly run its course by 3:30 a.m., when the destroyed

hulk grounded close to a bank on the Arkansas side of the river, about

three miles down river from the explosion site. Thirty-five people were

saved from the still-burning prow of the craft in Arkansas. Alerted

rescue brigades of citizen boaters and canoeists were now in the river

and along the flooded banks looking for survivors. The Navy and other

boats from Memphis were also now helping. The grounded Sultana burned

to the water level and sank below the surface of the flooded Mississippi

within minutes of the removal of the last injured survivors from the

prow of the boat.

It is undetermined how many died in the disaster, but the Sultana still

remains far and away America’s worst inland marine disaster ever.

More people were lost on the Sultana than the Titanic sinking in 1912.

Life after the disaster

Besides Maddux and Tolbert, Jefferson County, Ind., had a number of

other citizens on the Sultana. Among them were father-and-son James

Safford Sr. and James Safford Jr. The elder Safford was a member of

the Christian Commission, while his son was enlisted in the 10th Indiana

Cavalry.

Capt. James Walter Elliott, born in “South Hanover,” also

survived, and it was an injured Elliott who organized a large contingent

of Indiana and Ohio prisoner survivors of the Sultana disaster and saw

them safely to Cairo and Indianapolis and Columbus, Ohio. It was Elliott

who intervened with Indiana Gov. Oliver P. Morton in fastracking the

Saffords, Tolbert and Maddox back to Jefferson County. The latter two

arrived in Madison by rail on May 6, 1865.

The Saffords moved from the county soon after the war’s end, but

both Tolbert and Maddox continued their lives in Jefferson County and

both lived well into their 70s. Tolbert is buried in the New Bethel

Cemetery in Saluda Township, while Maddux was buried on the family farm.

Slowly, the terrible memories dimmed for those who experienced the terror,

pain and agony of that night in April, 1865, on the flooded Mississippi

and lived to tell about it. The national news accounts of the disaster

also faded quickly. In fact, the disaster made only incidental and marginal

news.

America was simply swamped with other momentous news during April 1865.

Lincoln was assassinated and the funeral cortege took three weeks to

cross the country from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Ill. John Wilkes

Booth was slain in a barn in Virginia. Lee surrendered at Appomattox.

Confederate Gen. Joe Johnson surrendered soon after Lee, effectively

ending the Civil War.

Military inquiries into the cause of the Sultana disaster were only

lightly covered by the newspapers of the day. So America’s greatest

inland marine disaster became mostly a historical footnote to the American

Civil War.

• Robert Gray, 77, resides in Saluda Township in western Jefferson County, Ind.